From the Steps of the Gazelle to the Steps of Ghazal:

On the Meaning of Meaning:

Re-rhyming Rumi

Rumi’s timeless poetry stirs in the spirit those who don’t turn in the body in search of the divine within. In Islam’s rich literary tradition the Sufis have carved a niche of their own. Because of the powerful pull of this tradition, many poets have eventually become Sufis whereas Rumi was a Sufi who eventually became a poet.

Poetry in general and Sufi poetry in particular is not translatable. What is commonly referred to as translations are renditions of one of the many possible interpretations of the poet’s thought and inspirations that are versified, re-rhymed, or free-rhymed outside of the original linguistic milieu. Thus, one must be linguistically and culturally immersed in both traditions to comment on poetry in this regard. A.J. Arberry for one meets this criterion of bi-culturalism, for instance, when he writes that Rumi is “one of the world’s greatest poets. In profundity of thought, inventiveness of image, and triumphant mastery of language, he stands out as the supreme genius of Islamic mysticism.”

But even then, much of the poetry, at best, remains permanently straddled across cultural divides. Here are two examples from the Persianate Islamic world:

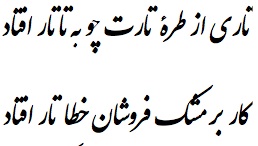

taar-i az turra-i taarat chu ba tataar uftad

kaar bar mushk firoshaan-i khita taar uftad.

Alas, a string of your dark tresses might traverse the territory of Tartary,

(if so) its abundance will surely cause the collapse of the musk trade in Cathay.

In spite of the attempt to catch the allophonic resonance, the poetically imbedded nuances and niceties of the beauty of thought of the original don’t carry over to the new vernacular. Add to that task the complexity of thought, which may be deliberately expressed ambiguously like Rumi’s quatrain on Hallaj.

The controversy of Mansur Hallaj’s claim saying, “I am the Absolute” has remained unresolvable throughout Islamic history. The never-ending debate has been and still is as to whether Hallaj literally claimed Divine identity or his divinations and spiritual exhortations had any of the many possible alternative interpretations. Rumi adds to the confusion of mind and the infusion of thought by intentionally playing on the double entendre of the lexicon and the cross-cultural ambiguity of poetic nuance.

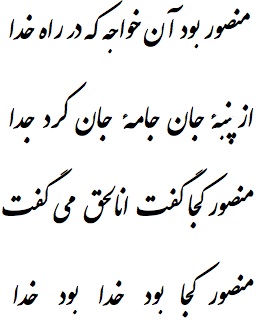

Mansur bud aan khaja ke dar raah-i khuda

Az pumba-i tan jaama-i jaan kard juda

Mansur kuja guft ana al-Haq miguft

Mansur kuja buud khuda buud khuda

The above quatrain, which has intentionally not punctuated can be literally translated as follows:

The distance between the two beings one lost, one ineffable i.e., Mansur not knowing himself, God being the unknowable, we being lost as to know where each of the two entities are, asking Mansur to question himself, and asking him to the whereabouts of God, questioning the independence of each entity as a whole in the gamut of mystical thought.

That literal form of the first two hemistiches, in spite of the mystical metaphor, make a clear statement:

Mansur was the master who in the path of God separated the garment of the soul from the fiber of the body.

It is the last two hemistiches that render numerous interpretations and turns the clarity of thought on its head, especially when it is Mansur Hallaj’s head (life) that is on the line:

Where did Mansur say’ I am God,’ he said: Where was Mansur (where) there was God (Mansur was nothing and nowhere)

Mansur wasn’t anywhere, but God was always there (everywhere)

Mansur wasn’t God, but God was (God)

Where is Mansur (now), (but) God was (has always been God).

(Where is) Mansur, God was there, God was there

Where did Mansur say ’I am God,’ he said (as a calling): Mansur is nowhere, I am God, I am God.

Ponder perpetual perplexities.